From the middle of the seventeenth until the middle of the nineteenth century, the Dutch were the only Europeans allowed to trade with Japan. Since nearly all of the academic knowledge that reached Japan from the West arrived in written Dutch, the Dutch language became the language of science in Japan during this period. How did they learn the language? What practicalities did they face? And what impact did Dutch have on the society and intellectual life of Japan? Christopher Joby gives the answers in The Dutch Language in Japan (1600-1900). Reinier Salverda, Honorary Professor of Dutch Language and Literature, read the book. ‘Page after page, one encounters the same delightful scholarship, with which Joby sets a standard that will last long.’

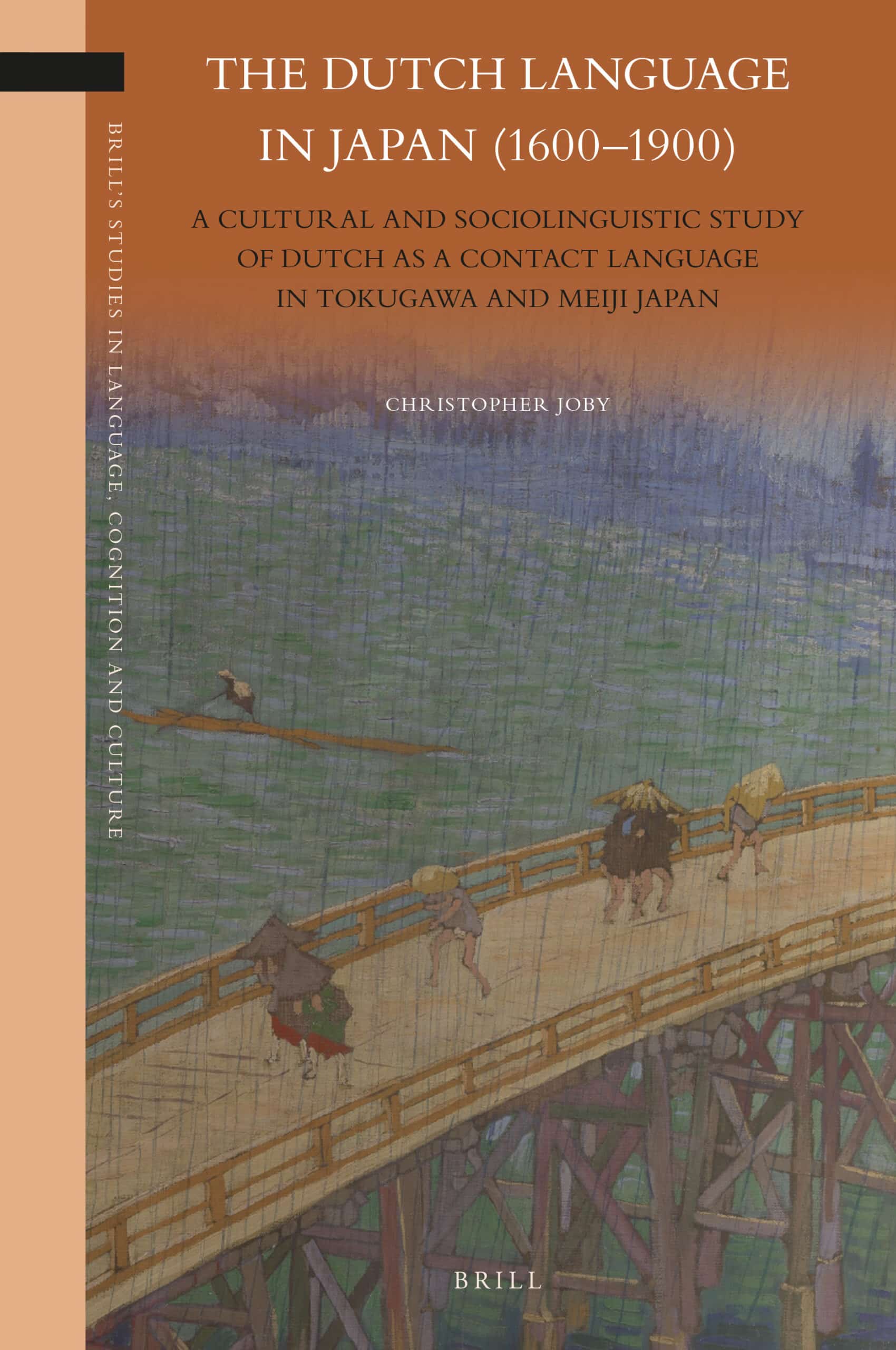

Our starting point is the authoritative judgement by Marius B. Jansen, Professor Emeritus of Japanese History at Princeton University, in his The Making of Modern Japan: ‘The story of the struggle of Japanese to learn more about the West from the Dutch is one of the most extraordinary chapters in cultural exchange in world history.’ (Jansen 2000, 211). It is this story of Rangaku (Dutch Studies in Japan) which is the central topic of Christopher Joby’s masterful new book, published in January by Brill: The Dutch Language in Japan (1600–1900). A Cultural and Sociolinguistic Study of Dutch as a Contact Language in Tokugawa and Meiji Japan.

After his PhD in History from Durham University in 2006, Joby in 2014 and 2015

produced two solid monographs on language contact and cultural connections between the Dutch and the English in the 17th century [see my review in The Low Countries 24 (2016), 290–292]. He is currently Visiting Professor in Dutch at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań.

Painting by Kawahara Keiga: Arrival of a Dutch Ship. Philipp Franz von Siebold at Dejima with his Japanese wife Otaki and their baby daughter Ine observing a VOC ship in Nagasaki Bay using a telescope

Painting by Kawahara Keiga: Arrival of a Dutch Ship. Philipp Franz von Siebold at Dejima with his Japanese wife Otaki and their baby daughter Ine observing a VOC ship in Nagasaki Bay using a telescope© Wikipedia

In the first half of the book (chapters 1 to 4), Joby is laying the groundwork – presenting basic sources, primary data and language documentation; identifying relevant disciplines and questions, leading up to the issue of language contact as the central focus in chapter 4; surveying situations, languages, people and processes which were involved at the time – all in preparation for his more detailed investigation of the outcomes of Dutch-Japanese language contact which are covered in the second half of the book.

The Prologue (8–15) offers a helpful series of chapter summaries, in which Joby also identifies four key reference points for his enquiry – first, in Cultural History: Peter Burke’s studies of Early Modern European Multilingualism; next, in the field of Translation Studies: Theo Hermans’ views on the History of Translation, together with the studies by Rebekah Clements and Wolfgang Michel (1985 to 2003) on Translation from Dutch into Japanese in Early Modern History; third, in Contact Linguistics: contributions from Thomason & Kaufman’s Contact Linguistics to Languages in Contact by Lim & Ansaldo; and finally, in Rangaku (Dutch Studies): Henk de Groot’s PhD of 2005 and the many Japanese sources on Dutch language learning discussed in it.

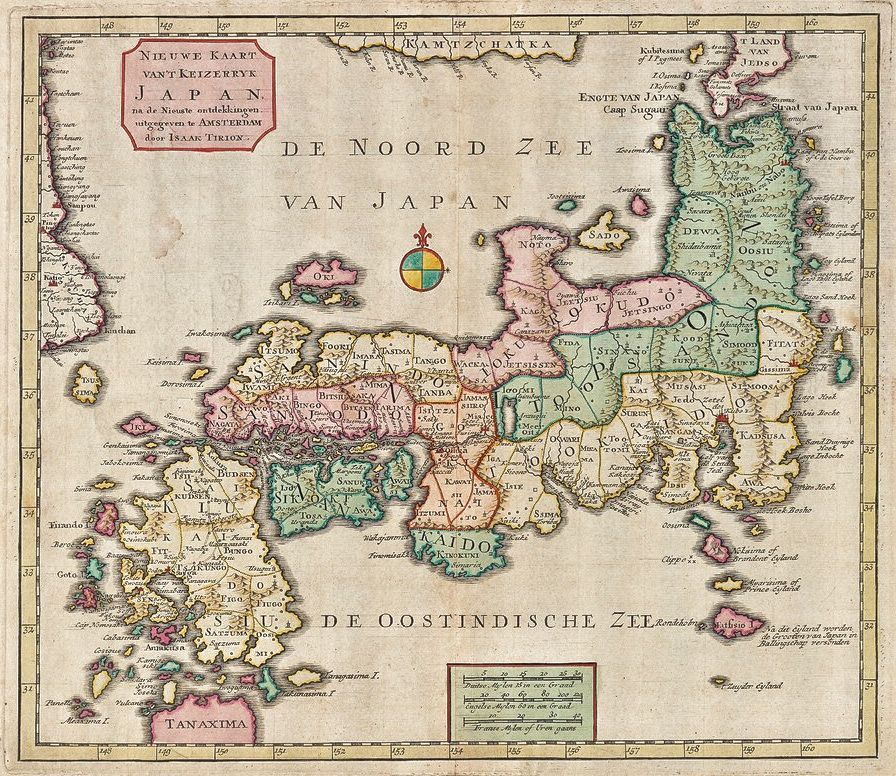

Antique Dutch map of Japan, 1740?

Antique Dutch map of Japan, 1740?In chapter 1, Those Who Already Knew Dutch in Japan (16–43), Joby introduces a number of key figures, Dutchmen such as Titsingh and Doeff, Germans like Kaempfer and Von Siebold, and the Swedish naturalist Thunberg – demonstrating how the Dutch presence in Japan occurred in an international and multilingual setting, where Dutch was in competition with other languages present (European as well as Asian), while its speakers were involved in processes of language learning, translation and code-switching, as they tried to establish contact and communication with speakers of other languages.

Chapter 2, Learning Dutch in Tokugawa Japan (44–88), focuses throughout on Japanese learners of Dutch during the period 1603-1867 – who they were, how they did it, what practicalities they faced, how schools developed and operated, and what learning materials they produced, such as word lists, lexicon, grammars and pronunciation guides. All this on the basis of original Dutch and Japanese sources; of previous studies, e.g. by Michel of the intermediary role of European medics and physicians based in the Dutch trading station at Deshima; and in particular also of the accounts of Dutch language learning left by Japanese rangaku scholars, including the difficulties they faced. Thus, Joby relates the tale of the botanist Gotō Mitsuo (1696–1771), who in his book of 1765 on Dutch culture and science, Oranda banashi (= Dutch Tales), included a Table of Dutch letters, in Gothic, Roman and Italian script, with approximate equivalents of their pronunciation in katakana characters underneath. So, how do we know if he captured the actual pronunciation of its Dutch speakers or, rather, what its Japanese speakers made it sound like? As if this was not difficult enough already, the Tokugawa administration decided his book was barbarous and dangerous, and so confiscated and destroyed it. Fortunately, however, some copies survived (cf. also Illustration 11 on 392).

The Dutch trading station at Deshima, Kawahara Keiga (workshop of), c. 1833 - c. 1836

The Dutch trading station at Deshima, Kawahara Keiga (workshop of), c. 1833 - c. 1836© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

From chapter 3, The Many Uses of Dutch in Japan (89–149), we learn more about the ways in which Dutch was used in Japan. Here Joby brings in Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia for the different voices and many lects which he distinguishes. At the time, the Dutch used it in record keeping, journals, correspondence and everyday conversation amongst themselves. The Japanese used it for language learning and artistic purposes; in letter writing, book collecting, map-making and as a vehicle for acquiring and handling Western knowledge.

Chapter 4, Language Contact

(150–203), presents what is the central issue of the book, with a fascinating series of portraits of the languages then coexisting with Dutch in Japan – Japanese, Portuguese, Latin, Malay, Sinitic varieties, Korean, Ainu, German, Russian, Manchu, French and English. This complex language environment provided the sociosemiotic context within which Dutch functioned and competed with other languages, in particular Portuguese and Chinese.

In the second half of the book (chapters 5 to 8), Joby presents more in-depth analyses of the outcomes of this Language Contact – ranging from Language Learning and Translation, through Lexical Interference in Dutch from other languages, and Interference from Dutch into Japanese, all the way to Language Shift and Recession in the 19th century.

Chapter 5, Interference in Dutch Texts (204–254), deals with a host of contact issues involving lexical interference. A key process here is that of phonological adaptation to their mother tongue by Japanese foreign language learners (214–217), as in Japanese madorosu from Dutch matroos (sailor, cf. 347). Similar processes operated in the opposite direction too, witness toponyms with Dutchified adaptations from Japanese such as Nangasacki (from Nagasaki), Firando (for Hirado) or Jedo

(for Edo).

Five Dutch men having a meal, anonymous, after Rin Shihei, 1790 - 1810

Five Dutch men having a meal, anonymous, after Rin Shihei, 1790 - 1810© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Pursuing this further in chapter 7, Lexical,

Syntactic and Graphic Interference by Dutch in Japanese (309–395), Joby gives a formidable 40-page list of Dutch loanwords in Japanese (335–375): more than 600 entries, across a wide range of lexical domains, each given in romaji alphabet, with their Dutch origin, English equivalent, source publication and date of first record, culled from a further list of some 70 original Japanese sources published between 1724 and 1897 (328–331). Of great interest here are the many loan translations, loan shifts, loan blends and native creations (352–373). There is, however, no alphabetic list of these loans, and I was unable to find Japanese otemba (tomboy, rebellious woman) which – as we know from Blussé (1986, 259) – comes from Dutch ontembaar.

Description of a microscope in 'Various stories about the Dutch', 1787

Description of a microscope in 'Various stories about the Dutch', 1787© Wikipedia

Meanwhile, chapter 6, Translation from Dutch (255–308), further develops the cultural history and translation studies angle of Joby’s investigation. During the Rangaku period, more than one thousand books were imported from Holland, in many fields that interested the Japanese elite: in botany and medicine, in astronomy, chemistry and physics, in language learning and dictionaries. Many of these were translated into Japanese, and Joby gives a very good idea of the incredible complexities and difficulties of the translation processes involved.

In the last chapter 8: Language Shift and Recession (396–425), we enter the 19th-century period, when the Dutch position in Japan declined through increasing international competition from western competitors, until in 1853–1854 US Naval Commander Perry put an end to three centuries of Japanese isolation and seclusion, and the Dutch trading monopoly.

Kapitein: Hollander die naar het Oosten is gekomen, anonymous, c. 1700

Kapitein: Hollander die naar het Oosten is gekomen, anonymous, c. 1700© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In his Epilogue, Joby’s concluding message is clear. In language history, the issue of language contact is central. Language historical questions, consequently, require a multidisciplinary approach, involving not only history (e.g. of colonial expansion, world trade, cultural contact and exchange (of books, for example)), but equally contact linguistics and historical sociolinguistics; language learning and interference; translation studies and lexicography. That is, when studying Dutch language history, we need to take on board that we do so always in a multilingual context.

The many interesting results Joby has produced in the pursuit of this new, multidisciplinary approach to the case of Rangaku, are underpinned by a formidable scholarly apparatus. To begin with, there are his many detailed footnotes throughout the text; his list of Illustrations (p. xv-xvi), his Indexes of Japanese, Chinese and Other Names, and his helpful two-page Glossary (p. xvii-xix) of key Japanese terms used in his text, from bakufu (‘Shogunal administration’) to Yosho shirabesho (‘Office for the investigation of Western Books’), all in Roman script, Japanese characters and with English explanation.

Joby gives a very good idea of the incredible complexities and difficulties of the translation processes involved

Next, there is his richly informative ‘Index of Japanese Primary Sources by Title’ (465 – 474), which lists some 200 works from the Rangaku period, giving their titles in rōmaji and Japanese characters, with English translation, year of publication, ID number in the online database of the National Institute of Japanese Literature, and where possible also its Dutch source text, author name, translator and editor. Here – or in the Bibliography, which lists Rodrigues’ Arte da Lingoa de Iapam (1604) – it would have been useful to also include the important Jesuit Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam (1603), with its modern Japanese translation, Tadao, Doi; Morita Takeshi & Chonan Minoru (eds.). Hoyaku <<Ni-Po jisho>>. Tokyo, Iwanami-shoten, 1980.

Then further, there is Joby’s well-thought-out nine-page ‘Index of Subjects and Places’ (486–494), with entries ranging from ‘Phonological system’ and ‘Pronunciation’ (under ‘Dutch’, 487) through ‘Interpreters’, ‘Lexical contact phenomena, typology’ and ‘Printing at Nagasaki’ to ‘Christianity’ and ‘Servants and slaves’.

Great praise, then, for Joby’s wide-ranging, solid and impressive new study

And then, there is Joby’s impressive multidisciplinary and multilingual Bibliography (431 – 464), in Japanese and Dutch as well as English, German, French, Latin, Portuguese and Russian. The four core disciplines mentioned at the beginning are all well represented, while Joby ranges further still when he includes Jonathan Israel’s discussion of the Enlightenment’s coming to Japan in his Democratic Enlightenment (2011, 572–582).

Looking forward, Joby, in his Epilogue

(425–430), suggest a few desiderata: further study of Code Switching in Japanese; of Rangaku

sources not yet covered; and of language contact between languages other than Dutch and Japanese. What he really would want is to apply the methodology used in this Japanese case to other such historic situations of multilingual language contact. So, taking this cue, could we envisage, one day, a contact linguistic study of the history of Dutch in Indonesia (the former Dutch East Indies) in comparison with other such cases of Dutch in a multilingual setting – as was common around the world in key localities of the former Dutch maritime merchant empire, such as New York, Batavia, Cape Town, Curaçao, and Amsterdam (cf. Salverda 2013, 2018)?

Great praise, then, for Joby’s wide-ranging, solid and impressive new study – for its clarity of structure, its thoroughness of substance and apparatus, its innovative combination of disciplines and the depth of analysis this has made possible; for his exemplary grip on this complex subject matter, with its multitude of data, detail, sources, languages and speakers; for the force of his conclusions on the impact this contact with the Dutch has had on Japanese culture and society; and last but not least, for the quality of his many well-chosen and beautifully reproduced illustrations. Page after page, one encounters the same delightful scholarship, with which Joby sets a standard that will last long. His book is a major contribution to Japanese and Asian Studies, and will strongly appeal also to scholars in many other fields, such as Dutch studies, book history, translation studies, European expansion, colonial lexicography, multilingualism, and above all contact linguistics.

Bibliography

Blussé, Leonard. Strange Company. Dordrecht: Foris, 1986.

De Groot, Henk. “The Study of the Dutch Language in Japan during Its Period of National Isolation (Ca.1641-1868).” PhD dissertation, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2005.

Israel, Jonathan. Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights, 1750-1790. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Jansen, Marius B. The Making of Modern Japan. London & Cambridge MA: Harvard, 2000.

Salverda, Reinier. “Between Dutch and Indonesian: Colonial Dutch in Time and Space.” In The Dutch Language in Time and Space, edited by F. Hinskens and J. Taeldeman, 800–821. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013.

Salverda, Reinier. “Dutch and Other Languages in 17th Century Britain and the Dutch Republic”. In: The Low Countries

vol. 24 (2016), 290-291.

Salverda, Reinier. “Empires and Their Languages: Reflections on the History and the Linguistics of Lingua Franca and Lingua Sacra.” In Studies in Multilingualism, Lingua Franca and Lingua Sacra, edited by Jens Braarvig and Mark Geller, 13–78. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, 2018.

Christopher Joby, The Dutch Language in Japan (1600-1900). A Cultural and Sociolinguistic Study of Dutch as a Contact Language in Tokugawa and Meiji Japan, Brill, Leiden & Boston, 2021, 494 pp.

This article first appeared in Dutch Crossing, Journal of Low Countries, Volume 45, 2021